December 28th, 1925. Leningrad. Hotel Angleterre

In Room No. 5, early in the morning, a man is found dead, hanged by his own belt. That’s what the official report says.

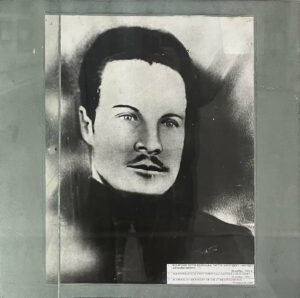

The man – young, handsome, famous.

Under his left eye, a dark bruise. A swelling on his forehead. Hands – scratched, as if he had fought back. The room ransacked. Furniture displaced, blood stains on the wall. The dead man’s name is Sergei Yesenin.

His spirit was a storm. His work was a hymn to the earth, to Russia, to humanity.

His end is a riddle that still defies all answers.

Yesenin is Born in 1895 in the Russian countryside into a simple peasant family, surrounded by fields, horses, rivers, and the hard and honest work of the land.

These roots shaped him forever. This world, rough and sacred at once, would later become the heart of his poetry – a longing for truth and for the human.

But Sergei Yesenin was not just a peasant with a pen. Another strive burned within him- a strive for life, for motion, and for expression. He wanted to step out into the city, Into the vast, loud, and confusing outer world.

In 1912, Yesenin moved to Moscow.

At seventeen years of age and driven by his desire for life, freedom, and creation he arrived with a suitcase and notebooks full of poems.

He worked in a printing house during the day and in the evenings attended lectures at the Shanyavsky University. This University was founded in 1908 by philanthropist Alexander Shanyavsky and his wife Lydia, who donated their entire fortune to ensure education “for the people.” The idea was revolutionary- learning for everyone, not just the rich or noble.

In Moscow, Yesenin wrote tirelessly, sending his poems to countless publishers. Most went unanswered. A few appeared in minor and obscure journals.

The “peasant poet” felt invisible, unseen, and unacknowledged. Moscow, absorbed in politics and philosophy, had little room for his voice.

“They read my verses, but they do not hear them,” he said about Moscow.

That realisation became the spark to leave Moscow for Petrograd.

In 1915, Petrograd (the former St. Petersburg, today’s St. Petersburg) was the beating heart of Russian literature. It was home to great publishers, magazines, literary circles, and salons. There lived those Yesenin admired the most: Alexander Blok, Andrei Bely, Anna Akhmatova, Nikolai Gumilyov, Osip Mandelstam.

Anyone who wanted to be heard had to be in Petrograd. And so he went.

With the simplicity of his native the countryside and his audacity, Yesenin went directly to Alexander Blok, without invitation, without announcement.

Blok was already famous. Yesenin was unknown and young, and with his clear eyes and audacious charm, he stood at Blok’s door.

Blok wasn’t home. Yesenin left a note « I will come at 4 p.m. » as if it were the most natural thing in the world for Russia’s most celebrated poet to wait for a boy from Ryazan. And Blok actually received him later.

Yesenin arrived wearing a simple peasant shirt, a coarse belt, dusty boots – as if he came straight from a field.

Blok later said of him: “He came from Russia itself.”

Yesenin read his poems calmly, clearly, without theatrics, half prayer, and half song.

From that moment, Yesenin was no longer unknown. Blok’s “blessing” opened the doors of literary Russia.

Here began his poetic journey – the rise in history and at the same time the descent of his own life.

Publishers began to print his poems. He read in literary salons, on stages, in crowded rooms, where workers, students and intellectuals alike heard for the first time in simple words what they themselves felt but could not express.

There his reputation grew, not only as a poet, but as a wild and untamed spirit. He spoke as he felt – unmade up, honest, sometimes rude. And Russia listened to him because he spoke as the people felt.

He became the voice of a time about to vanish – the memory of an old Russia sinking beneath the noise of a new age.

1917.Revolution

The old Russia, with its churches, bells and fields, was swallowed by the roar of the new world. At first, the people – and Yesenin with them – greeted the Revolution with hope.

He believed it would liberate the simple folk about whom he wrote, and from whom he came. But soon he realised the new Russia spoke a language he did not understand.

The churches stood empty, the bells were silent, and where prayer had been, now stood command. He saw how the new power did not heal the old, but erased it.

He watched the people he loved march now under red banners, not from the heart, but in step.

“I waited for a song – and heard boots,” wrote Alexander Blok.

Yesenin felt the same.

For him, this was no liberation, but a new kind of captivity. In Petrograd – once the temple of literature – the voices that had filled the air fell silent.

The great poets were gone, exiled, or dead. The city that had once embraced him like a son had grown cold and foreign.

It was a rupture – not only in history, but in human thought. The Revolution changed not just the land, but the language, the art, and even the meaning of words.

Yesenin could not fit among the new, politically thinking poets. He was too human for the cold ideologues of the new age. The poetry of the time turned into slogans, programs, revolutionary odes – without warmth, without soul.

In 1918, Yesenin returned to Moscow

He stayed by old friends, read at literary gatherings, drank, provoked and searched desperately for new meaning. His poems began to sound like reflections of a shattered self – full of tenderness mixed with anger, homesickness and defiance. From this turmoil came his sharpest verses about Russia, the people he loved, and the new era he no longer understood.

His fame lived on, but something in him began to die.

That same year, he joined a new literary movement: the Imaginists, from the word image. Together with Anatoly Marienhof, Rurik Ivnev, and Vadim Shershnevich he sought a poetry that didn’t preach, but glowed.

“The word should not serve – it should shine,” – wrote Shershnevich.

Yesenin was the soul of the movement: passionate, contradictory, untamed.

His verses pulsed, breathed, and smelled like earth after rain. He wrote as if holding Russia itself in his hands, warm, heavy, incomprehensible.

At night, Moscow’s taverns were their temples, filled with smoke, laughter, arguments about art, God, and the new world. Their words were sparks: beautiful and dangerous.

But soon the brilliance turned to exhaustion. Conversations became quarrels. Inspiration turned to excess. What began as rebellion ended in chaos.

Yesenin felt there was no salvation here either. Everything he had tried, from art, love, fame, and intoxication left him empty. Inside him remained only the bitter void.

And then she came: Isadora Duncan

They met at a literary evening in Moscow.

Isadora was a woman from another world, famous in Europe and America, a dancer, a dreamer, a revolutionary. She came to Russia to open a dance school for children of the people and give them freedom and expression through movement. She believed in the same idea Yesenin had once believed in: the Revolution as a promise of freedom and human dignity. Their meeting was like the collision of two worlds.

Isadora was instantly captivated by his golden curls, youthful beauty, and wild, untamed aura.

She didn’t understand Russian but she understood him.

And he was dazzled by this woman, who danced barefoot and fearless before the world. She was seventeen years older than he. She called him tenderly “my golden head”.

He reminded her of her son Patrick, who had died tragically in 1913.

Both came from ruins, she from personal grief and he from spiritual exhaustion after the Revolution and the collapse of his faith in the new world.

They were not seeking each other but redemption. Instead, they found a mirror.

It was love at first sight and downfall at second sight.

After their wedding in 1922 came a restless time- Paris, Berlin, Venice, New York. They travelled from stage to stage, from receptions to interviews, from champagne to …quarrels. The world cheered Isadora and saw in him only “the handsome young Russian at her side.”

In Russia he was Yesenin, the poet. In America he was no one.

“Over there, I’m only Mrs. Duncan’s husband,”- he said bitterly.

The early fire faded into misunderstandings, scenes, and a deep loneliness of two people together. Yet Isadora loved him truly. She protected him, forgave his outbursts, his drinking, his disappearances. Her love was almost maternal.

He, however, felt trapped, restless, defiant, and unpredictable. Friends later recalled how he mocked her accent, her age, her fame. He vanished for days, drank, fought, and she waited and forgave.

But Yesenin wanted no chains, neither of marriage nor of obligation. This love became a burden.

Later, he admitted: “I did not love her – I tormented her.”

When they returned to Russia in May 1923, the flame was already dying. By late 1923, they separated.

His fame in Moscow returned. Applause returned. But so did the crack in his soul, deeper and unhealable.

He spent his nights in smoky kabaks (taverns) among poets, musicians, street girls, and lost souls. The Moscow police knew his name too well. Fights, drunken brawls, arrests became routine.

He was detained, released, and by the next night, back again with fire in his eyes and vodka in hand. From his chaos he forged poetry:

“I am drawn to everything that is torn apart – only the living can tear.”

“I have spent more nights behind bars, than in beds that are called love,”- he joked bitterly.

His poems grew sharper, his words braver. He mocked officials, ridiculed the new morality, wrote what others didn’t even dare think.

Too loud. Too free. Too honest.Too dangerous.

The new powers began to watch him. He knew it and wrote on anyway.

“I have learned to tell the truth, even when it cuts my throat,” he wrote in a letter.

Autumn 1925. Yesenin travels by train from Baku to Moscow

In his carriage sat diplomats: Alfred Roga, a courier of the Foreign Ministry, and Yuri Levit, an acquaintance of the influential functionary Lev Kamenev.

The evening began with talk of poetry, ended in arguments over politics. Yesenin, half drunk, spoke bluntly, too bluntly for that time. He mocked the regime, spoke of hunger, hypocrisy, and betrayed ideals.

“The Revolution has devoured its own children” he is said to have declared.

A formal complaint was filed against Yesenin, accusing him of “publicly insulting state officials.” A trial awaited Yesenin and its outcome was all predictable.

His friends persuaded him to disappear: not to flee, but rather to hide.

He was admitted to the psychiatric clinic of the Moscow University Hospital under the supervision of Professor Gannushkin. Officially, it was “for treatment” for alcoholism and alleged mental instability. In reality, it was an attempt to protect him: from the courts, from the state and from the “new world” he had once believed in.

He kept writing even there. “I’m letting Russia treat me,”- he joked bitterly.

Later, this stay became the perfect pretext for the legend that would cover his death: “He was mentally ill. Depressed. An alcoholic.”

After his release in November 1925, he stayed with friends, preparing a new edition of his writings, spoke of the future. Tired but still alive.

Nothing suggested a man preparing to die. And yet, a few weeks later, his name reappears in Leningrad. How or why he went there remains unknown.

28 December 1925 Yesenin is found dead in his room at the Hotel Angleterre.

Hanged by his own belt. So says the report.

But the details speak otherwise. His name does not appear in the hotel registry. He was never officially checked in. In the Soviet Union, where every guest was documented, such absence was impossible.

Historical note: the Hotel Angleterre stood directly across from the headquarters of the GPU (the State Political Directorate, the Soviet secret police that preceded the NKVD and KGB) in Leningrad, a detail that is impossible to ignore.

The room was a wreck. Blood on the walls. A bruise on his temple. Scratches on his hands: signs of struggle. The ceiling nearly four meters high, too high to hang oneself.

He was found suspended from a smooth, vertical heating pipe. One hand was stiff near his throat, as if frozen in a final attempt to free himself from the noose.

Artist Vasily Svarog, who soon after molded Yesenin’s death mask, said the posture resembled “a man in fight.”

Today that plaster mask is preserved in the Yesenin Museum in Konstantinovo, his birthplace. A mask that permits no lie.

Many researchers and biographers still doubt the official version to this day.

Too many contradictions. Too many falsified documents. Too many unanswered questions. The investigation files are still classified.

“I am no coward,” he once wrote, “I live loudly and die standing.”

Prophetically, in the Land of Scoundrels

And years before, prophetically, in The Land of Scoundrels ,1923 (banned from publication between 1930 and 1980), Yesenin wrote:

Мне до дьявола противны И те, и эти.

Я потерял равновесие…

И знаю сам – Конечно, меня подвесят

Когда-нибудь к небесам.

Ну так что ж! Это ещё лучше!

Там можно прикуривать о звёзды…

(Странa негодяев, 1923)

Translation:

To hell with them – both sides disgust me.

I’ve lost my balance…

And I know myself – someday they’ll hang me,

up to the very heavens.

Well then – so be it!

All the better!

Up there, I can light my cigarette from the stars.

Julia’s view

Yesenin was a storm, the fiercest hooligan of Russian poetry but never a coward to end his life that way.

What we are left with today is the official version: suicide.

Because it’s easier that way to glorify the power that destroyed him.

They say those who take their own life remain suspended between earth and sky. Their souls find no peace because they themselves extinguished their right to light.

But if it was not he who took that light from himself, but others who stole it then his soul has remained for a hundred years a prisoner of a lie.

He, who fought in his verses for truth, for freedom, for the human soul remains, even in death, a hostage of injustice just as he was in life.

Perhaps peace will come only when the truth is spoken.

Not for history.

For him.